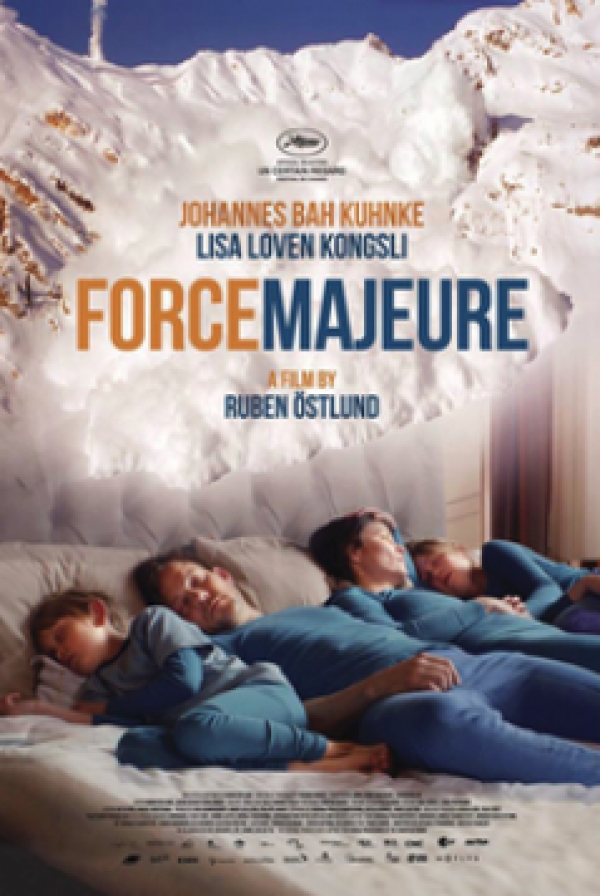

The film Force Majeure focuses on the tensions within a marriage, but it also depicts the tensions between people and the natural environment.

The original Swedish title of Ruben Östlund’s internationally acclaimed film Force Majeure is Turist, which is „Tourist“. The pivotal drama in the film is the moment early on when an avalanche of snow threatens to bury the winter holiday makers having a meal in a good restaurant in the Alps: the husband grabs his phone and gloves and runs away, but the wife tries to protect their two children. This incident forces marital tensions to the surface, and leaves hanging the question implicitly posed in the French title of the film.

Beyond doubt the central relationship in the film is between Ebba, the wife and her husband Tomas. It is not a National Geographic presentation about mountains. However, the film does have a strong sub-theme about our relation to the environment, which in many ways parallels that between Tomas and Ebba. The original Swedish title arguably implies this, but that meaning gets lost in the French title.

The opening sequence, intercut with the credits for the film, brilliantly expresses this juxtaposition of relationships. A tourist photographer cajoles and organises Tomas, Ebba and their sweet-looking children Vera and Harry, all in their skiing gear, into a series of ever more idealised family poses against the spectacular backdrop of the mountain snowscape, while throughout the chairlift rumbles by in the top left of the screen, like a factory assembly line. A cut then shows the ski resort from a distance in a low sun, depicting the stunning beauty of snow-clad peaks against a cloudless blue sky. However the same shot also shows how precarious the resort is, sitting between a glacier and a sheer cliff. The pure white snow of the slopes is dotted with trails of chair lifts and ski runs. Neon lights flash monotonously, remorselessly but almost abstractly in the resort, then a cut depicts huge metal tubes that have been driven into the top of the mountains, tubes which then emit explosions to trigger controlled avalanches.

Just as the cohesive family is finessed into an image by the professional wearing the yellow jacket with “Photographe Touristique” on the back, so also the mountain landscape is manipulated as a spectacle to be consumed by the tourists. While that process of consumption can appear passive, just like the family’s pose, it depends on an aggressive intervention into a pristine environment, processed through machinery of various types to make the place a commodity, which affluent people from Sweden (the photographer begins by asking “Where you from?”) and other faraway places will pay to experience. Soon, the explosions will set the snow rolling towards the balcony restaurant, which gives splendid views the scenery, where the family are dining, simultaneously upsetting the equilibrium of the family and of the landforms.

The touristification of the snow paradise is regularly depicted in images that are both comic and threatening. Giant snow ploughs ascend and smooth the slopes in the apres ski hours. A tunnel leading to the resort resembles a giant orange caterpillar. The scale of the multi-story hotel dominates the village. Ski helmets and goggles in particular, along with the huge boots and puffy clothing transform the family into aliens, literally masking them behind hi-tech’ equipment. Harry’s latest expensive toy, a drone circles above the resort before literally crashing his parents’ dinner party. Travellators screech. Gadgets proliferate, and even the electric toothbrushes sound jarring.

Like everything else, even the act of skiing, the equipment is about control as well as consumption. It is not a coincidence that Tomas grabs his phone and ski gloves when he thinks the avalanche is going to hit the restaurant, or that he compliments Harry for being “in control” when flying the drone, or that the youngster is frustrated when he cannot get a network for his tablet. Just when they need to get into their bedroom to open, the smart key won’t open the door and a faintly menacing cleaner has to let them in. The mechanised landscape provides the control that enables the snow and mountains to become a spectacle and a playground.

The contrast is when Tomas and his friend Mats head off piste to relive their youths and re-bond in the wilderness after a difficult night for both of them with their respective partners. There are some amazing shots of the pair of them, tiny figures, trudging up a near vertical wall of snow, leaving their footprints, their heavy breathing as the soundtrack in the thin, blue air. The visual beauty of their skiing here comes with the comment “It doesn’t get any better than this”, and the eventual catharsis for Tomas.

There is a final people/environment twist as the holiday makers are driven in a coach down the mountainside along a narrow road of hairpin bends. As the drivers lurches the vehicle forwards and backwards, anxiety rises and Ebba snaps, abusing the driver and demanding to get off. The other passengers also panic and disembark. The bus heads off down the tortuous slope ahead of them, while the foreigners walk towards the way home.

This sequence has some ambiguities: is the driver really as bad as Ebba claims, or is the process of inching the big vehicle back and forth to circumvent the bends just the way you have to do it? Viewed as Force Majeure, the decision to walk is an existential response to a life threatening situation. But viewed as Turist it looks more like an endemic mistrust of the rich visitor towards the competence of the local population, a loss of control once such people rather than machines and gadgets stand between us and the landscape of danger, even death.

In summary, the film can be enjoyed in different ways. Critics rightly focus on the main plot lines around inter-personal relationships, but to me the film is enriched if we see those relationships intertwined with our relationships to places, or more specifically the relationships of affluent consumers to the places they colonise. Exposure to nature, in all its extremes, can indeed be liberating, but what is it liberating us from, and how has the natural landscape itself been shackled to afford the opportunity for human liberation? Writing this during the 2020 lockdown, our response to the avalanche of disease that rushes towards us, and which was unleashed by our intense global connectivity and ability to control places and people, this film seems like an epitaph to a time and an industry that so recently absorbed us. Today’s pandemic exposes the fragility, even deceit behind that moment in time, just like Ebba and Tomas’ holiday photo of the perfect family, and eve perhaps like Sweden’s own image of tolerant affluence.

Other film reviews on this site:

Mr.Tree – A tale from the new China

Prefab‘ Story – High Rise, Mud and Shoddy Housing

Schreibe einen Kommentar