Dr.Michael Kordas provides insights into the use of charettes for participation in planning – before and after Covid 19.

Dr. Michael Kordas provides this guest blog that raises important questions about how the changes forced by the Covid 19 pandemic might impact on participatory methods like charettes.

My doctoral research investigated the impact of the planning and design charrette in Scotland. The devolved Scottish Government provided funding to local authorities to ‘mainstream’ these events into practice throughout the 2010’s, making Scotland the ideal case study of the ‘visions for’ and ‘realties of’ participation in a contemporary planning system. Since defending my work at Viva, the world has seen seismic changes that have caused me to reconsider the findings of my research and reframe my recommendations both for the current situation and hopefully, a future post Covid.

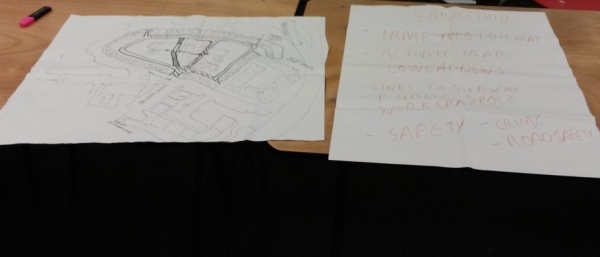

Charrettes in Scotland curiously, have both defied and been bound by the conventions of Western planning systems under neoliberalism. Most positively, the charrette’s position in the ‘mainstream’ of nationwide practice put planning and design issues ‘on the radar’. In some cases, hosting such a high profile participative event served to focus the attention of decision makers, particularly those in command of regeneration and project funding, on a place. The practice of doing charrettes evolved in itself. As the format developed in Scotland, facilitation teams began ‘setting up shop’ on the streets and town centres of host communities in advance to harness local interest. Some of my case study events stood out in bringing professional and community participants face to face, either through working over maps and sketches together, or experiencing the host places ‘live’ on walking tours and site visits. They were able to build a highly charged and vibrant participative atmosphere in which local people were encouraged to re-engage with the heritage of their places and reconsider what their place meant to them.

Nevertheless, mainstreaming support in Scotland caused something of a consultancy industry to materialise around participative planning, with budgets routinely extending into the tens of thousands of pounds. Some places in fact, had multiple charrettes over several years with no clear continuity between them, raising the spectre of over-engagement or ‘consultation fatigue’. In others, charrettes succeeded in legitimising significant expansions of development land over and above the existing planning strategy. Yet others, claimed to offer an open forum or ‘blank slate’ to discuss development issues, but steered the outcomes of the process toward existing strategy and its conventions, despite the concerns of local people. Ultimately these questions forced me to reconsider whether charrettes and similar workshop events offer something genuinely ‘new’ in participative planning? Where planning strategy is directed, as in the current Scottish policy, towards ensuring ‘sustainable economic growth’ with all the ambiguities this term raises, perhaps this was no surprise. If land and property development is effectively ‘the public interest’, it becomes challenging for planners to take on-board the views of the communities who do not agree such development is necessary. Likewise, it is all too easy to see participation by public event as merely a checklist exercise, with no real commitment to following up with local people as plans and strategies proceed.

As I write this article, the future of the idea of participative planning and design as a face to face activity seems to be in question. Certainly, physical distancing measures seem to count against the ‘in person’ dynamic of methods like the charrette. When planning participation does happen, it will likely need to be conducted remotely and online for some time to come. Yet, this situation also creates the opportunity for new ways of participating in planning that might address the failings of doing so by public event that my research identified. So what could a post Covid future hold, if it is not too early to imagine such a future?

My research suggests what I term a ‘three dimensional’ approach to participative planning and design. Such engagement would incorporate sustained feedback loops between local people and planners. The goal of participation therefore becomes not a one-off ‘checkbox’ in the production of a new plan or strategy, but the formation of a network of locally interested parties to more gradually build the plan through repeated critical review. As such, the model moves toward to John Friedman’s ‘transactive’ planning, where practitioners are prepared to respect the lived experience of local people alongside their own professional knowledge, but also to accept critical feedback and be prepared to re-visit plans and strategies as works in progress to ensure they meet local needs. This vision for participation is highly compatible with physical distancing and remote working online. It could proceed by adapting existing project management and co- production technologies, as are common in the tech’ and further education sectors. Taking a long term approach to developing new plans and strategies would permit all interested parties to participate at a time suiting them, overcoming the need to attend one or a series of real world events.

Ultimately, this form of long term engagement could be difficult to swallow politically in any post-Covid world. The need for economic recovery will likely threaten processes that create complications to property development and the construction industry, with this sector a standby of government intervention and already a priority in current plans for re-opening. However, as the Covid crisis has shown, society at large is highly adaptable to switching to both working and socialising from home. Planning practices and policies need to be prepared to show this same level of flexibility lest the ‘new normal’ becomes simply a repeat of the old ‘business as usual’.

Michael Kordas MRTPI is a planner and data analyst with extensive professional experience in regeneration project work, development management, heritage conservation and building regional spatial strategy. Michael holds a PhD in Urban Studies from the University of Glasgow in Scotland, gained through working in, and researching, community engagement. He has also taught planning and urban design at the Glasgow School of Art. He can be contacted via LinkedIn at www.linkedin.com/in/michael-kordas

Schreibe einen Kommentar